Augusta Conchiglia on the Eastern Front Tracks

Curated by Maria do Carmo Piçarra and José da Costa Ramos

One autumn afternoon, somewhere in the possible intervals of a pandemic, Maria do Carmo Piçarra and José Costa Ramos introduced me to Augusta and her photographs of the Angolan liberation struggle.

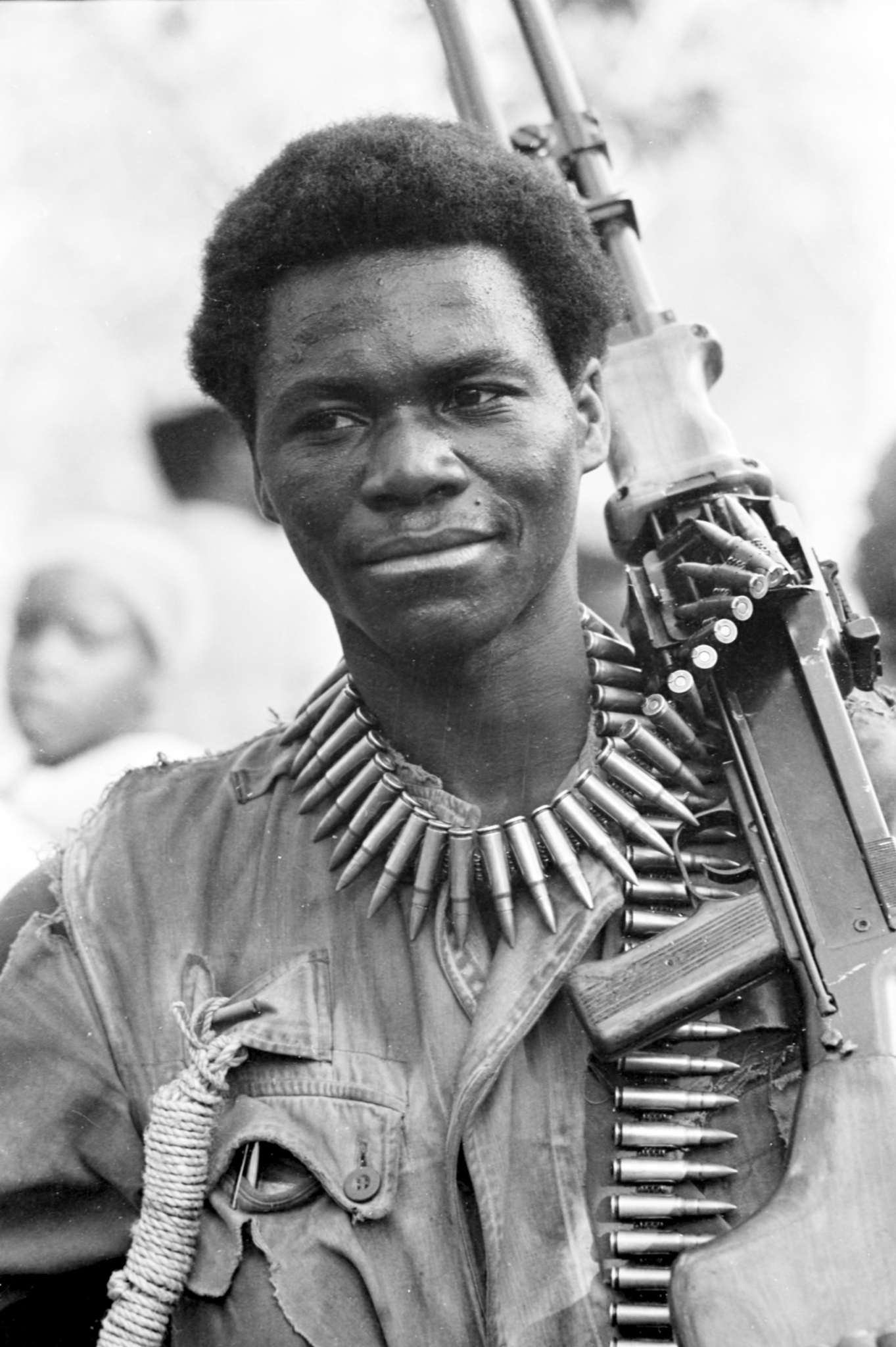

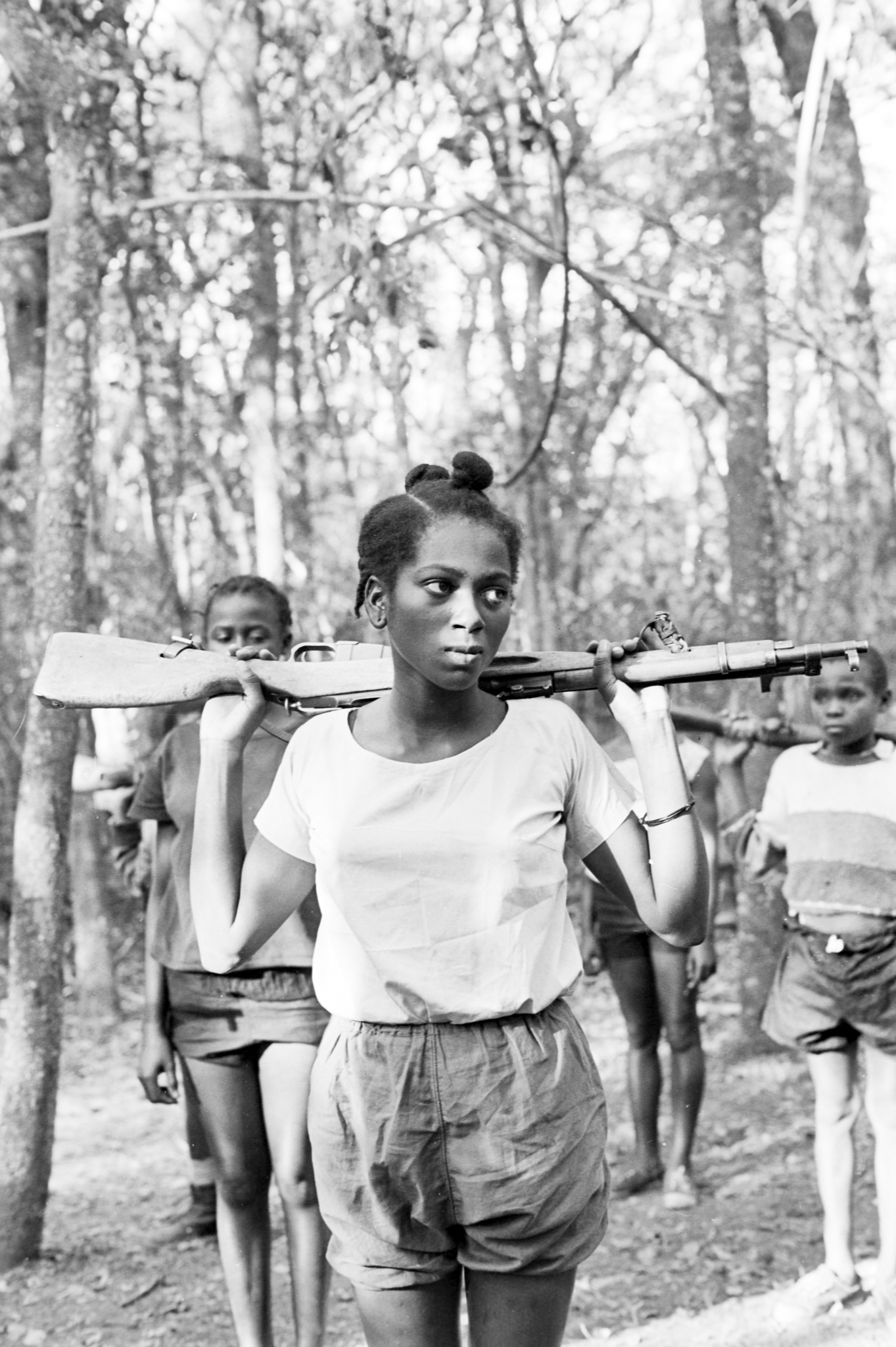

In Portugal, we never saw images of those who resisted for the liberation of their countries. It was through Augusta’s photographs that, for the first time, I saw the faces of the women and men who were forced to take up arms to conquer their freedom and independence. When I opened the files, I was struck by the power of those images, and soon realised the importance of sharing them with others.

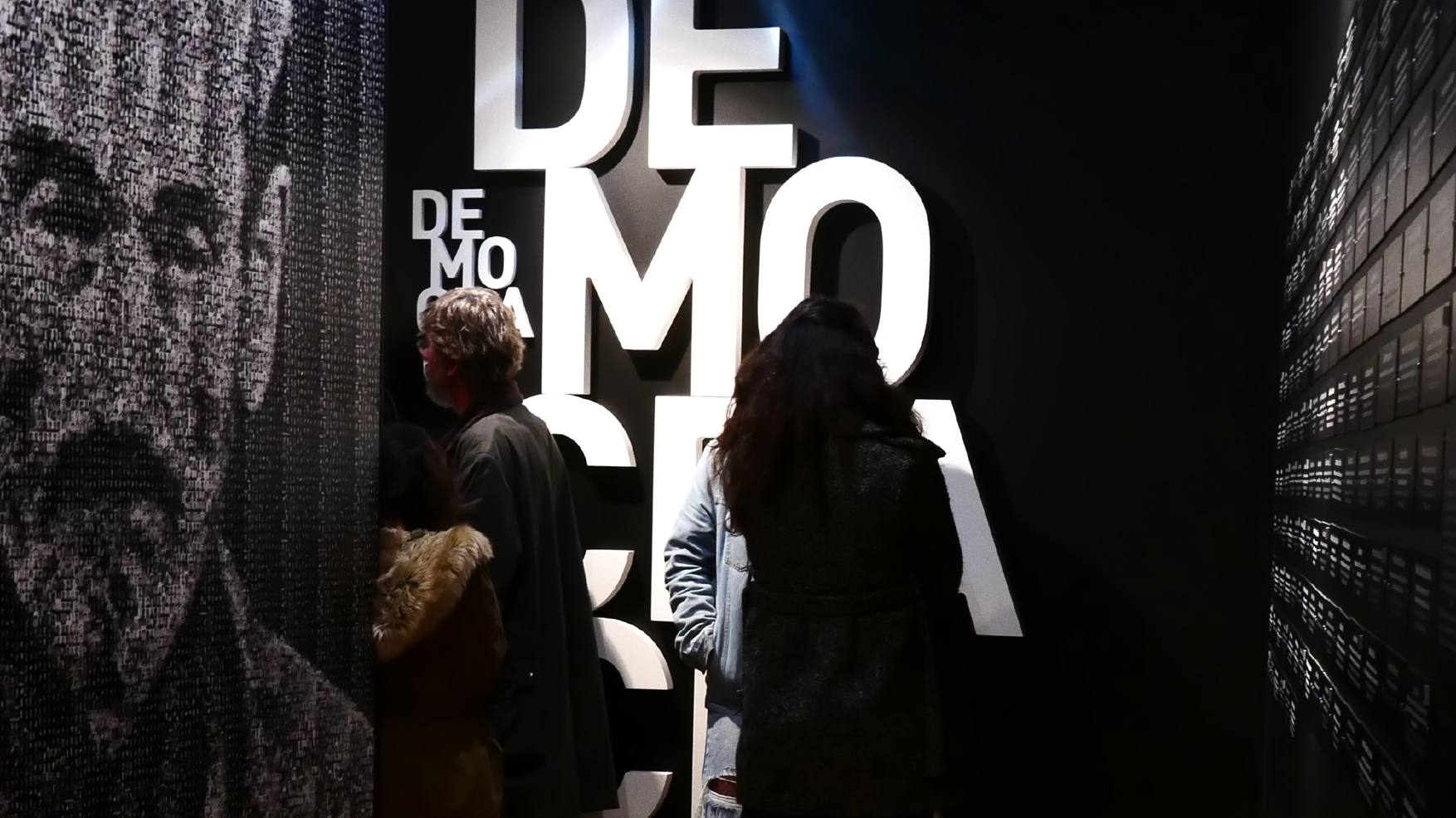

Sharing the story of an Italian photographer who decides to photograph the anti-colonial struggle, the other side, of the people who resist, of those who fight for independence, of those who join forces to fight colonialism and conquer freedom is also the mission of the Aljube Museum Resistance and Freedom.

“Colonialism, in its different eras and formulas, consisted of the domination of occupied territories, exercised over their respective populations, enslaved and harshly repressed, in many cases until their annihilation, with the aim of ensuring the exploitation of natural and mineral resources. The colonial power subjugated these peoples in the name of the supposed superiority of the white race and its “civilising mission”, imposing slavery and forced labour. It was only practically in the second half of the 20th century that the colonised peoples of Africa and Asia began to gain independence, almost always after difficult paths of resistance to the occupier”, one reads on floor 3 of the museum’s long-term exhibition.

On February 4, 1961, Luanda’s jails and police stations were attacked to free political prisoners. From March 15, massacres of settlers and their employees in the farms and villages of northwest Angola, carried out by UPA sympathizers, set Angola ablaze.

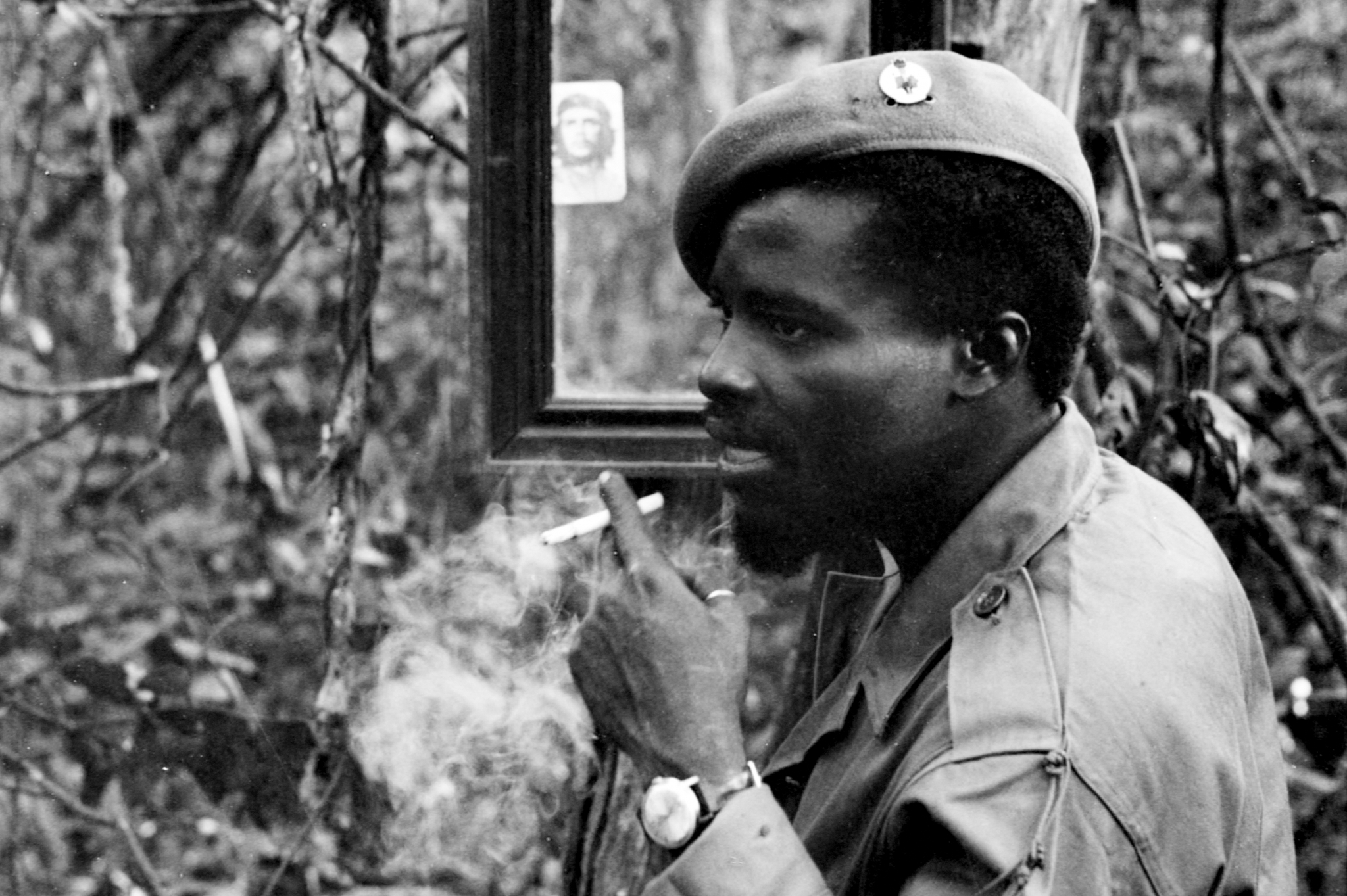

Seven years later, Augusta Conchiglia, an Italian photographer, accompanied by Stefano de Stefani, would travel for five months through places of resistance and of the liberation struggle of Angola, guided by MPLA guerrillas. These are the photographs that we will have the privilege of seeing in this exhibition, until December 2021.

To Maria do Carmo, José Costa Ramos and Augusta Conchiglia, many thanks for their revelation, generosity and sharing.

To all the women and men who fought against colonialism, for independence and freedom, this is a simple tribute of the Aljube Museum Resistance and Freedom.

Rita Rato, director of Aljube Museum

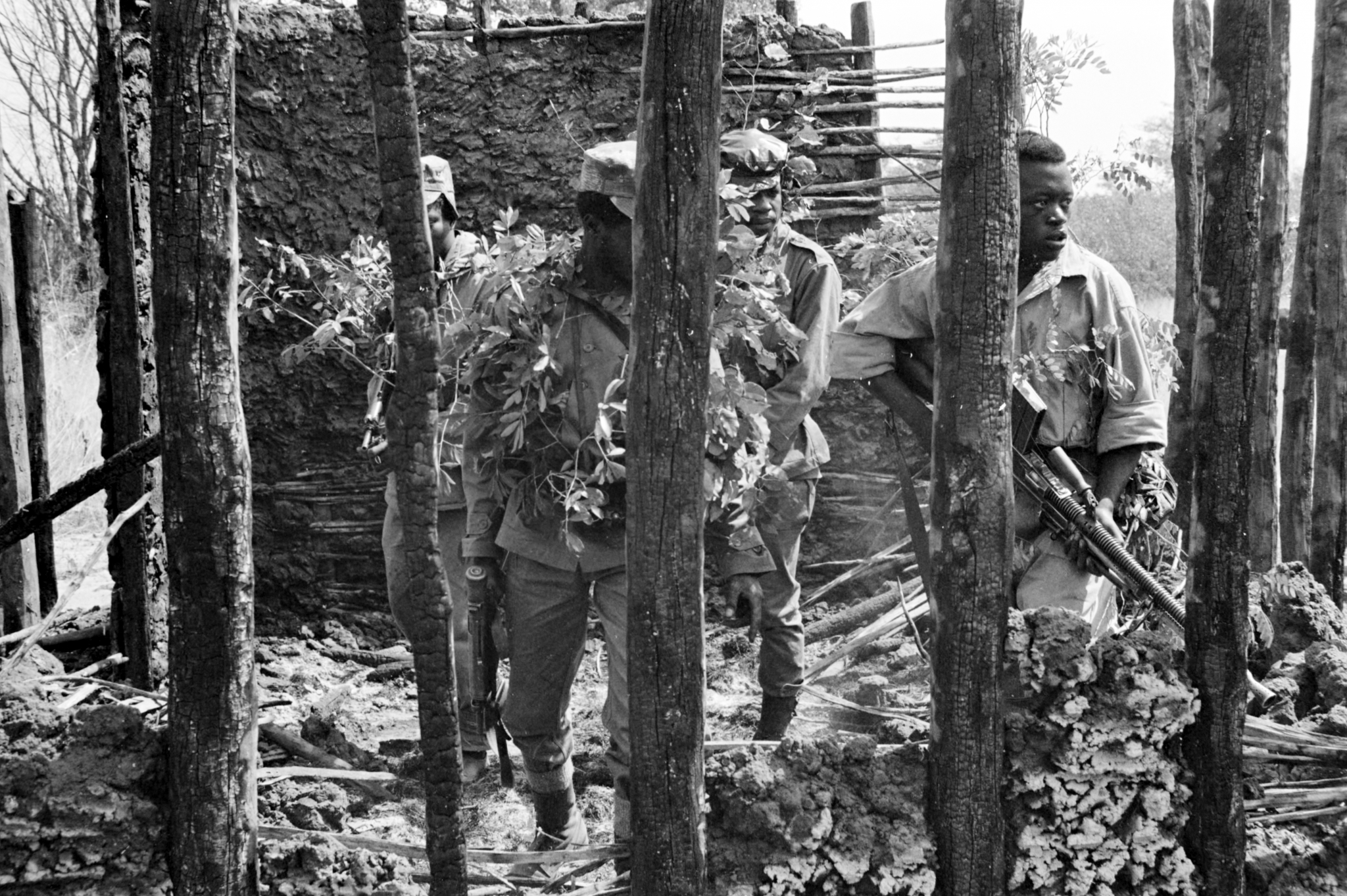

In April 1968, Italian journalist Augusta Conchiglia (1948) clandestinely entered Angola to report, together with director Stefano de Stefani (1929), on the ongoing liberation struggle. Until September, guided by the guerrillas of the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), they covered hundreds of kilometers in the liberated zones of Moxico.

With two Nikon F’s, Augusta Conchiglia took thousands of pictures, a small part of which were published in Guerra di Popolo in Angola / Guerre du Peuple en Angola (1969), a small format album, with Italian and Swiss-French editions – by Lerici, in Italy, and, in Switzerland, by MSACP -, whose subtitle makes it clear that it was a photographic reportage carried out with the MPLA guerrillas.

Curated by Maria do Carmo Piçarra and José da Costa Ramos, Augusta Conchiglia on the Eastern Front Tracks – Images (and Sounds) of the Liberation Struggle in Angola presents many of the images reproduced in what is credited as the first photographic album by someone outside the African liberation struggles. Published on the initiative of the Associazione per i Rapporti com i Movimenti Africani di Liberazione (ARMAL), founded in Italy in 1968, many of the photographs were reframed to enhance their effects and meanings. An analysis of the surviving negatives reveals that they were either reproduced with no or only slight reframing, or they were “cropped” in order to, in a variation that anticipates the “analytical (film) camera” (Gianikian, Ricci Lucchi), create close-ups. These reveal elements – such as the gaze – and make more expressive and meaningful details, both of human faces and bodies and of the integration of people in the landscape.

For this exhibition at the Aljube Museum – Resistance and Freedom – whose director, Rita Rato, enthusiastically welcomed the idea of presenting, for the first time, a selection of Augusta Conchiglia’s photographs, we digitalized, with the highest possible quality, more than a thousand existing black and white negatives – in 50 years, some were lost. In the print, we have restored the original framings to the photographs, sublimating more the humanism in the images and less the subordination of the same to the militant purpose, evident, underlying its taking and especially its later use, both in the aforementioned album and in posters, book covers, etc. Additionally, we have added to the iconic images, other unpublished ones, revealing the quality and sensibility of the author’s gaze.

Despite the hardness of the treks, the food shortage – resulting from the war, with the annihilation of the existing cattle by the Portuguese Army and the use of defoliants -, the rarefaction of medical assistance and the permanent risk of military attacks, the passage of Augusta Conchiglia in the maquis was not determined by the acceleration of the movement but rather by the urgency of fixing the daily life in the liberated zones. The intuition and sensibility are evident – the images denote the quality of the relationship with the people photographed, and the effort to reveal all aspects of the ongoing struggle. Although the reportage is framed by the militantism of the author, it highlights the portraits and the fixation of situations, simple or disruptive, of the daily life of the guerrillas and people in the context of the struggle. The literacy manuals, the weapons of one and the other (also to cultivate the fields); the maintenance of the same; their use(s) and integration of gestures – of their importance – in a collective movement of a community struggling for survival and liberation, but in which, nevertheless, Conchiglia does not stop looking at people in their singularity. She also does it when she portrays Agostinho Neto. She does not capture him in a pose; she portrays him both when he speaks and when he watches a representation of the colonial violence against the Angolans. The look on Neto is no different from the one on “Inga” Inglés, who became secretary-general of the Angolan Women’s Organization, or on the woman who, in a territory with a huge infant mortality rate, accumulates all the worries of the world in a frown, while a baby sleeps serenely in her arms.

Photographic journey through the liberated zones

Guerra di Popolo in Angola / Guerre du Peuple en Angola opens with a preface by the intellectual Joyce Lussu, Italian translator of Agostinho Neto’s poetry. Lussu lived in Lisbon in 1941 as part of the activities of the Italian Resistance. His anti-fascist struggle included anti-colonialism. It was in this framework that he met Neto’s poetry. He returned to Lisbon twenty years later with a contract to publish, in Italy, the work of Neto, then imprisoned in the Aljube. Lussu unsuccessfully requested an audience with Neto from Homero de Oliveira Matos, director of the PIDE. It was through Maria Eugénia Neto that he got some answers, in addition to unpublished poems.

Lussu was who encouraged Conchiglia and de Stefani, director of RAI programs, to report on the struggle in Angola, then almost unknown in the West.

After leaving Rome in January 1968, Conchiglia and de Stefani reported for Italian television in Egypt and Zambia, to support the Angolan project – RAI could not protect illegal entry in the then Portuguese colony – before arriving in Tanzania, in Dar es Salaam, where part of the MPLA’s leadership was based. From Neto, Daniel Chipenda, and José Condesse de Carvalho (“Joka Toka”), they received the framework of the political and social situation. It was defined in which zones they would register the advances of the struggle, anticipating possible filming of war actions against the Portuguese Army.

From Lusaka, in Zambia, they left for the Angolan border in a van. The trip, at the end of the rainy season, was the first indication that the physical effort would be constant. Two days later they arrived, at night, at the border base of Kassamba. Tiredness gave way to emotion with the prospect of entering “free Angola”. About thirty guerrillas commanded by “Joka Toka” went on a journey, on foot, with Conchiglia and de Stefani , to Cazombo and later to the bases Mandume II and III. For weeks, it was in Mandume III that they interviewed, photographed and filmed some commanders: Filipe Floribert “Monimambo”, Iko Carreira, Ciel da Conceição “Gato”, as well as “Joka Toka”.

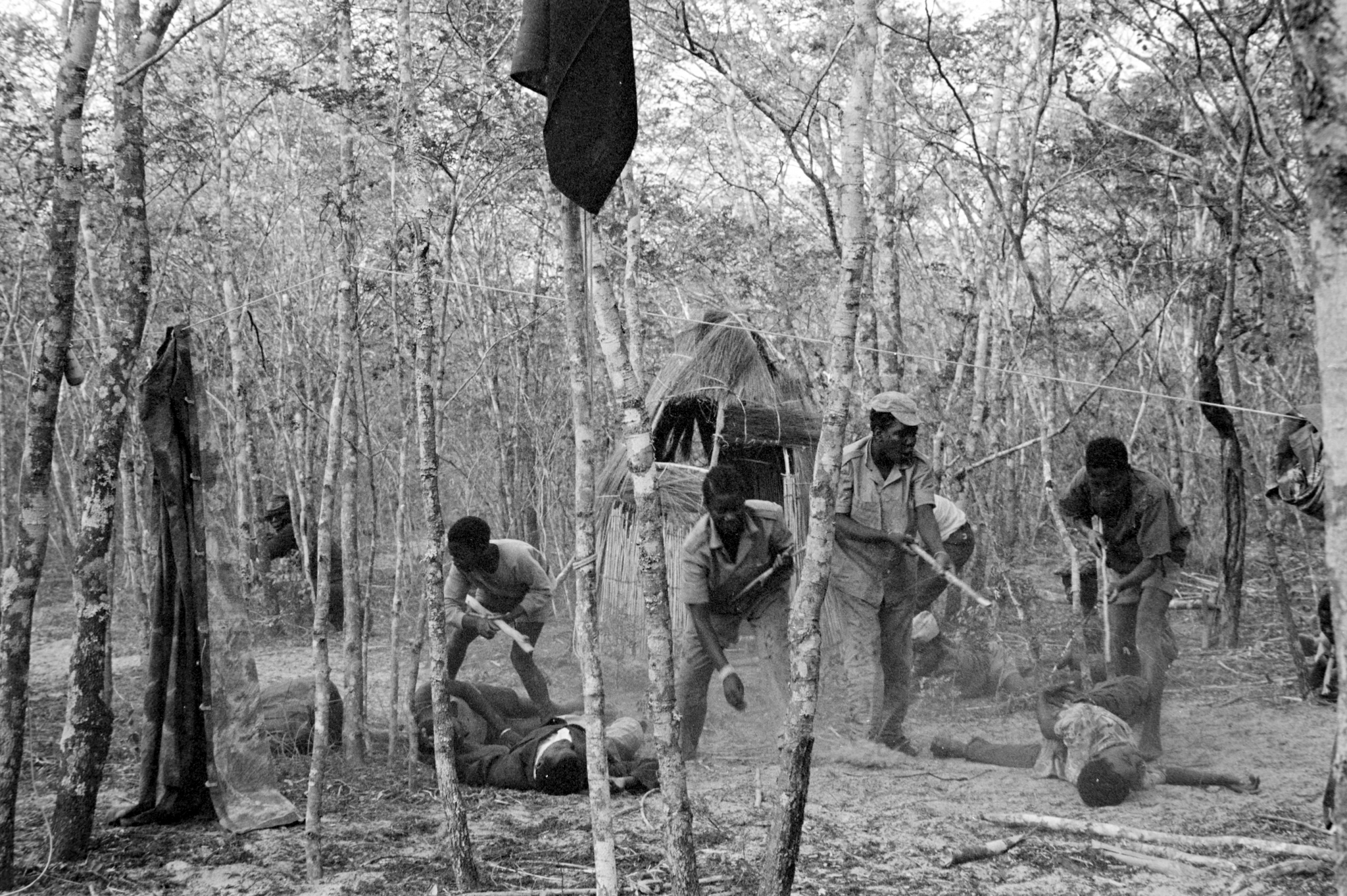

The most important bases had infirmary services and very basic schools for the pioneers. The oldest of them received military training armed with sticks, which replaced the scarce rifles. Not far away were the settlements, displaced from the traditional clearings, camouflaged in the bush, avoiding aerial reconnaissance and Portuguese attacks. The reporters documented meetings between the guerrillas and the population mediated by translators speaking Tchokuwe and Luvale – often it was necessary to resolve issues related to the ploughs. They also recorded the politicization sessions held by the guerrilla chiefs because the creation of bonds of unity was a priority. The idea of a nation was then an abstraction for those who questioned what improvement its genesis would bring to the life of each individual. The enormous diversity of people from various parts of the territory also translated itself culturally, and was revealed in the dances and dramas that enlivened life, hard, in the maquis.

The second stage of the trip – made at night, in the open, through the savannah, and including crossings of lagoons formed by heavy rain in canoes – took them to zone C, in the region of Lumbala-N’guimbo, south of the Eastern Front, where, from 22 to 25 August, the first conference of regional delegates in the liberated zones took place, with the presence of Agostinho Neto and with Aquino de Bragança as a guest. Other historical leaders of the MPLA attended, including Aníbal de Melo, Américo Boavida and “Dino Matrosse”. The location was not far from the road used by the Portuguese military to resupply one of their barracks, and so MPLA ambushes were planned, to be documented by de Stefani and Conchiglia. Successive days of waiting did not fulfill this expectation but did provide for conversations with the guerrillas to gauge what hopes they had for post-independence life.

Sounds of the struggle

In this first trip, several types of records were collected on magnetic tape and later published by ARMAL with Edizioni del Gallo, in the LP Angola Chiama, which has, on the cover under red background, an image by Augusta Conchiglia, of some performances – the reconstruction of an ambush on a Portuguese column during a dramatization of the liberation struggle and the representation of the demonstration that took place at the time of Neto’s arrest -, the interrogation of a Portuguese prisoner, the appeal of a Portuguese deserter on the program “The voice of Angola combatant” on Radio Tânzania, the discussion of an operation plan. Side 2 of the disc compiles sound recordings of dances, militant songs, testimonies of two peasants and a peasant woman (on the importance, for the MPLA, of the role of women in the struggle), a meeting with the population, and a course of revolutionary instruction in the liberated zones. A selection of these recordings dialogues in the exhibition with sequences of images or with certain photographs, allowing for a mental montage that Conchiglia and de Stefani objectified in a first version of the filmed materials was made for projection at the 1969 Panafrican Festival in Algiers, and later disappeared.

In 1970, Conchiglia and de Stefani clandestinely re-entered the liberated zones in Angola, accompanied by a small group that included Lionello Massobrio. They intended to make a color film about the MPLA’s struggle. A disagreement between the team led, however, to the duo making, in black and white, A Proposito dell’Angola – made collectively but attributed to Stefano di Stefani and whose whereabouts I have since located at the Istituto Luce-Cinecittà – which combines images filmed in 1968 with others from 1970. The trip also resulted in the publication, in Italy, of a second book with the same name as the film.

The disc Angola Chiama includes a booklet with a letter from Agostinho Neto, July 30, 1969, concerning the recent recognition, by the African Liberation Committee, of the MPLA as the only legitimate and representative movement of the interests of the population regarding the aspirations for independence. This circumstance framed the organization of many of the events and initiatives that the duo of reporters recorded. From the international recognition came increased responsibilities and in this period literacy, political education of the people and the guerrillas, organization of food production and implementation of radio communications were stimulated, while a strategy for international political relations to be established was determined. It is this phase of great dynamism of the MPLA, therefore, the one documented photographically by Augusta Conchiglia.

Augusta Conchiglia’s images – used, with credits, by Sarah Maldoror, in the closing credits of the first short film Monangambé (1968), and by William Klein in Festival Panafricain d’Alger (1969) – are iconographic of the struggle against Portuguese colonialism. After Angola’s independence, they were often used without credit to their author. This exhibition is also an act of restitution, in the sense that it projects the name of the author with her images.